Why is employee engagement important? Why does disengagement matter?

The Gallup organization, in systematically and comprehensively surveying workers across the United States in their State of the American Workplace, discovered an alarming insight: 70% of American employees – almost 70 million people – are disengaged in their work, leading to $319 billion in lost productivity and a $450 billion negative impact to the economy. Even worse, 19% of employees are actively sabotaging their employers. The localization of where the disengagement is happening in our organizations is highly troubling as well. “Engagement levels among service employees — those workers who are often on the front line serving customers — are among the lowest of any occupation Gallup measured and have declined in recent years.” The very workers who are closest to the most important people our organizations are designed to serve – our constituents, our customers, our clients – are at the highest risk of disengagement. This fundamental disconnect at the frontline of our organizations presents direct risks to the core mission of any organization. Think about the lost human potential and the impact of these statistics on the average person’s daily life.

Not surprisingly, Gallup also found that the 25% of workers who are engaged came up with most of the innovative ideas, created most of a company’s new customers, and had the most entrepreneurial energy.1 These organizations created the work conditions to harness the full potential of their employees to adapt to change and succeed in today’s complex work environments. What if more organizations could access this creativity and direct this effort towards their core missions? Beyond profitability and productivity, what kind of impact could another 70 million engaged workers have on our society? What problems that we currently face could be solved with all of this unutilized creativity, energy, and effort? How would it fundamentally change our society?

Most of what passes for leadership and management in today’s work environments are outdated Industrial Age ‘technology’ and is, in many ways, the true source of these is engagement statistics. In this paper, we will explore the root causes of this disengagement and outline how leaders and managers can adopt new insights from the latest research to increase engagement in their organizations. We will look at three strategies for improving engagement through leadership development:

- Clearly and consistently communicate the organization’s purpose and how the employee’s work connects to this purpose.

- Actively engage leaders through experiential learning and development.

- Emphasize managers’ strengths through regular feedback.

In particular, we will demonstrate how strategic use of a new type of leadership development approach at all levels of the organization can improve engagement, productivity, and impact in the world.

Why are 70% of Americans disengaged at work?

To understand this problem, we have to look back at the way work has evolved. For most workers, the major shifts in their personal engagement in work started during the throes of the Industrial Revolution. Before the 19th century, most work was done on the farm, in small shops, and in cottage industries in the home. While the work was difficult and sometimes strenuous, the connection with the work and the end-user of the product or service was direct and personal. Based on the economic theories of specialization of labor, economies of scale, and competitive advantage, industrial work changed this dynamic significantly. As much as possible, complex manufacturing processes, previously done on a small scale by artisans, were separated into smaller, repeatable tasks. The management techniques of Fredrick Winslow Taylor’s scientific management theory and the assembly line of Henry Ford greatly accelerated this evolution of work and increased the efficiency of the workflow. But it came at a cost for the human workers involved in these repetitive, disconnected tasks. Productivity rates skyrocketed, but employee engagement plummeted. Later, the same automation process was used for white-collar work in corporate offices, the military, and public sector organizations. In large part, all creative, strategic work was elevated to the top of the hierarchy. For most people at the technician level, their work became so separated, segmented, and disconnected from the vision and strategy of the organization that it is no wonder they became disengaged.2 In an age of predictability, limited information, and large-scale production, this model worked—for a time.

Fast forward to our current day. This process of intellectual centralization in the name of efficiency has been exponentially amplified by information technology, complex algorithms, and artificial intelligence. Richard Sennett describes that, “especially in the cutting-edge realms of high finance, advanced technology, and sophisticated services,” genuine knowledge work comes to be concentrated in an ever-smaller elite in our society.

At the same time as this continued organizational centralization of intellectual work activity in our personal and social lives, we have witnessed an exponential growth of information consumption. We are living in an age of information abundance and complexity. These forces have led to greater unpredictability and a decentralization of communication into social networks based on affinity and interest. Change and the need for personal adaptation have become constant. Yet, our organizations and our centralized leadership styles and approaches to management have not evolved with the pace of information technology. Because the technology of management and our organizations have been built on some outdated science and understanding of human motivations, we see what Jacob Morgan aptly called the “employee engagement divide.” 3 As was seen very clearly in the financial crisis of 2008, the combination of organizational centralization, complex financial transactions, and disengaged workers led to significant systemic leadership and management failures at all levels to make effective decisions for the health of the financial system. Without a new approach to leadership and management for both private and public sectors, this divide will continue to have detrimental impacts on the individual employee, the mission of the organization, the economy, and our society.

How do organizations need to adapt to the Information Age?

Based on Gallup’s State of the American Workplace study, there are three key actions to strengthen managers, employees, and ultimately, organizations.4

1. Clearly and consistently communicate the organization’s purpose and how the employee’s work connects to this purpose.

Beginning with Henry Ford, the traditional approach to addressing disengagement from work has been to “compensate” the employee with more money, perks, and workplace well-being initiatives.5 While research has shown this works to a degree for routine tasks, for any other type of work it can actually become counterproductive.6 Executives, managers, rank-and-file employees – all employees regardless of their title – want to know their contributions and time matter. By clearly communicating where the organization has been and where it is going, employees will have a more intrinsic connection to their work and can better understand how their position directly contributes to the growth of the organization. This knowledge builds purpose and power into all levels of the organization, which in turn, motivates employees with a sense of ownership.

Returning to The Gallup survey, they found that, “at the end of the day, an intrinsic connection to one’s work and one’s company is what truly drives performance, inspires discretionary effort, and improves well-being. If these basic needs are not fulfilled, then even the most extravagant perks will be little more than window dressing.” 7

To develop engaged leaders at all levels of an organization, we have to think about the person beyond the old frameworks of the rational economic actor that is only motivated by compensation and career progression.

The Clearing’s team of leadership and management experts has spent the last 30 years working across the public, private, and non-profit sectors in numerous transformation and change initiatives. We use visual frameworks, called The PRIMES, to identify the primal or universal nature of humans at work solving complex problems.

Central to our understanding of motivation, we utilize the PRIME called STAKE to frame what engages and motivates individuals to action. To communicate what is at stake, the leader and manager have to understand through empathy what motivates their teams and employees at three levels: HEAD (intellectual), HEART (directional, intuitive), and WALLET (monetary, economic). These motivations can be positive (PULL) and negative (PUSH). Without this comprehensive understanding, the leader cannot engage and inspire their teams.

While old industrial models have largely neglected the heart that is motivated by a sense of purpose and vision, we need a leadership that empowers all levels with the big picture, the “why” of the work and integrates this into a person’s daily tasks. This type of leadership communicates to the heart of workers through a process of ENNOBLEMENT, clearly connecting the individual’s work, the organization’s mission, and ultimately, the positive impact the organization will have in the world. It directly addresses the problem of personal disengagement created by the Industrial Age management approaches.

Most traditional leaders may discount the importance of ideas like empathy and purpose as the negotiable ‘soft’ elements of the business. But as we learn more about the future of work, we understand that the heart is the engine of creative aptitudes necessary to adapt to our rapidly changing world. In IBM’s global survey of leaders – the largest survey of executives in the world – the top characteristic 1,500 public and private executives looked for in employees was creativity.8 This is logical, as an organization cannot develop creative employees that can rapidly respond to change and complexity without understanding what motivates them at a heart level.

2. Actively engage leaders through experiential learning and development.

A recent study estimated that “direct turnover costs are 50%-60% of an employee’s annual salary, with total costs associated with turnover ranging from 90% to 200% of annual salary.” 9 Some studies have shown this cost to be much greater for executive-level employees. The cost of turnover is not just financial. When a leader or manager leaves an organization, it loses knowledge, intellectual capital, and experience, which leads to a negative impact on morale.

By providing training, mentoring, and coaching opportunities, you show your leadership team that you are invested in them and in their success. According to Gallup’s research, “people who get the opportunity to continually develop are twice as likely as those on the other end of the scale to say they will spend their career with their company.” 10 Based on statistics and our experience, what is needed is a new type of leader that can make these necessary personal connections with employees, while continually growing and developing their own skillsets. Over 70% of the workforce reports to mid-level managers, not the C-Suite. Citing Gallup’s research, “a Leader’s engagement directly affects managers’ engagement and manager engagement, in turn, directly influences employee engagement. Managers who are directly supervised by highly engaged leadership teams are 39% more likely to be engaged than managers who are supervised by actively disengaged leadership teams.” 11 Transformation must occur from the top-down and the bottom-up of our organizations, especially any part of the organization that directly interacts with customers, partners, and outside stakeholders.

If your organization is still designed for the Industrial Age, what can you do to develop leaders and managers as coaches throughout your organization? Today’s leaders must be comfortable with setting direction in the face of ambiguity and learning new insights as they take risks on the field. At The Clearing, we have found that effective leadership development utilizes real-life experimentation. In time-bound challenges, analogous to a sports competition, participants take action “on the court” towards a vision of business outcomes – a “TO-BE” – and they receive training “in the locker room” to gain skills necessary to succeed in the challenge. This approach is depicted in our COURT-LOCKER ROOM PRIME. Most learning and development programs provide employees with the opportunity to get away from their day-to-day role to learn new models, tools, and techniques. The challenge is that while they have experienced a change, their organization still operates in the same way. It is easy to slip back into old habits and ways of doing things. Think of a rubber band that has been stretched then suddenly snaps back to its old shape. Even worse, when leaders do not practice using those new tools and methods, they get rusty.

To build more resiliency in the face of constant change, leaders and managers also need both theory and a critical perspective to succeed at their missions. Continuing the sports analogy, players need time in the “locker room” to learn the plays for future games and to revisit their past performances. Learning and development programs need to push participants to think strategically about the organization from the “10,000” foot level. At The Clearing, we call this approach to learning, IN-ON. Most organizations fall into the trap of getting so focused in the business (IN) that they never take the time to step away from the work and ask the tough questions about how the organization functions from a systemic perspective (ON). What worked? What didn’t work? What should we do next time? To learn and grow, leaders and managers need to spend time working ON the organization. The effective leader knows the appropriate balance between IN-ON and the importance of spending equal time learning and teaching mental models and frameworks that improve the intellectual performance of the team.

3. Emphasize managers’ strengths through regular feedback and coaching.

The old adage, “employees don’t leave organizations, they leave bad bosses” is often true.

Unfortunately, most people have had or will have a bad boss at some point in their career. Is there such a thing as a truly bad boss or is it simply an individual that may not have the necessary tools to handle constant change? It has been our experience that often it is the latter. These individuals don’t realize they are seen as bad bosses. They are usually very involved with their own tasks and may neglect the team they depend on or perhaps they focus too much time and energy on the daily tasks of their team. Both neglect and micromanagement can severely damage productivity, trust, and the team. In today’s world of information abundance and complexity, management has to operate as flexible as possible, respond quickly to changes in the external environment, and empower their team to make appropriate decisions based on best practices. To do this, the leader has to transform from “boss” to “coach.”

In the Information Age, where collaboration with new team members will be a constant challenge, the ability of the coach to quickly build trust among the team members will be critical. In this context, the coach needs to set an example of skill and expertise in the craft of the organization to build instant trust. He or she has to have a history as a top performer in the field of competition. Without this experience of doing the core elements of the work, the leader cannot have the authority to build strangers into a team and guide the group to higher levels of excellence.

Building on this trust between each individual and the coach, the coach needs to transfer that trust into the group and rapidly develop group loyalty. The coach gets the group to see the better qualities of their teammates and to play to each other’s strengths. To build this instant rapport, they create a sense of camaraderie and commitment to each other that transcends the immediate transactions or activities of the moment. The coach sees individual persons for who they truly are and gets the team to see these strengths as well.

While all high performing leaders care about their teams, what sets the coach apart is their genuine interest in the growth and development of the individual members of their team. The coach works to help new team members identify their strengths, weaknesses, and professional goals. In one study of 65,672 employees, The Gallup Organization found that those who received strengths feedback had turnover rates that were 14.9% lower than for employees who received no feedback (controlling for job type and tenure).12 The coach challenges team members by providing them with assignments and tasks in their areas of interest, which stretch them professionally and personally, causing them to grow and develop in the work. All along the way, the coach walks alongside the individual, giving them feedback at the right time for their personal development.

Conclusion

Our world is not standing still. We can either adapt our organizations to the new realities of technology and work or face the consequences of growing disengagement. To rise to the challenge, we need to rethink our perspectives on work and motivation. We need to communicate to the whole person and we need to develop the leaders of tomorrow that can rapidly and flexibly build teams to solve discreet, time-bound problems. We have to go beyond designing new software and applications to solve social and human challenges. The technology of leadership and management needs an upgrade. To do this, we need to redesign our learning and development programs that form our employees and adapt our methods of feedback to encourage creativity and strengths-based development. If we rise to this challenge, a whole generation of leaders and managers can be empowered to tackle the world’s most pressing and complex problems.

Bibliography

1. Report: The State of the American Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders, pg. 4. Gallup Organization. September 22, 2014.

2. Ibid. pg. 4.

3. Crawford, Matthew B. “Shopclass as Soulcraft.” The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology and Society. Summer Edition 2006.

4. Sennett, Richard. The Culture of New Capitalism. Yale University Press. January 31, 2007.

5. Morgan, Jacob. “The Single Greatest Cause of Disengagement.” Forbes Magazine. October 13, 2014.

6. Report: The State of the American Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders, Gallup Organization. September 22, 2014.

7. Crawford, Matthew B. “Shopclass as Soulcraft.” The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology and Society. Summer Edition 2006.

8. Dan Ariely; Uri Gneezy; George Loewenstein & Nina Mazar (2005-07-23). “Large Stakes and Big Mistakes, Working Paper” (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Working Papers pg: 05-11.

9. Report: The State of the American Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders. Page 27. Gallup Organization. September 22, 2014.

10. Carr, Austin. “The Most Important Leadership Quality for CEO’s: Creativity.” Fast Company. May 8th, 2010.

11. Cascio, W.F. Managing Human Resources: Productivity, Quality of Work Life, Profits. 2006 (7th ed.).

12. Report: The State of the American Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders, Gallup Organization. September 22, 2014.

13. Report: The State of the American Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders, Gallup Organization. September 22, 2014.

14. Asplund, Jim & Nikki Blacksmith. The Secret to Higher Performance. The Business Journal. May 3rd, 2011.

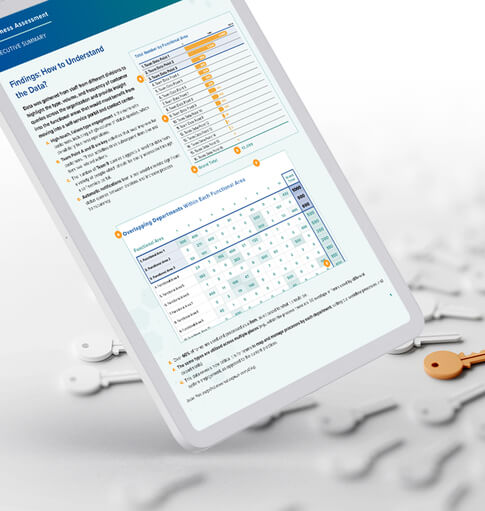

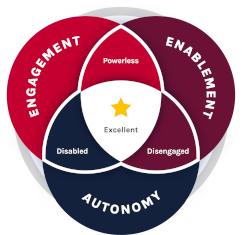

The Clearing’s Employee Experience

Improvement model, adapted from Itam

& Ghosh, 2020, focuses on three objectives:

The Clearing’s Employee Experience

Improvement model, adapted from Itam

& Ghosh, 2020, focuses on three objectives: