While it’s always nice when objectives are clear and all of the information you need to plan is at hand, that’s rarely the reality. Often, strategic planning occurs within ambiguous circumstances. As an Army Operational Planner in Afghanistan, Andy Dziengeleski learned to embrace this strategic ambiguity. Here, he shares his experience and tips for organizational planning under pressure. Senior leadership of any organization must work with their staff to understand the operational environment, take strategic ambiguity and complexity into account, and then craft an operational approach and plan that provides focus to the organization.

The Lay of the Land

In 2011, I was conducting my “payback” assignment after graduating from the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies. I had been assigned to the Future Plans Directorate of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Joint Command, otherwise known as IJC, and was learning my craft as an operational planner.

For those unfamiliar with the ISAF Joint Command, here is NATO’s description of the Command’s mission:

“ISAF Joint Command’s mission was to conduct population-centric comprehensive operations to neutralize the insurgency and support improved governance and development to protect the Afghan people and provide a secure environment for sustainable peace.”

IJC was a strange and unique headquarters – even for the military. It was extremely rank-heavy, with over 20 General Officers on the staff. By comparison, an American Corps Headquarters would have three Generals within the unit.

Additionally, it was not a typical Napoleonic staff, with functions broken out by numeric codes as identifiers, like the J (for Joint) 3 (for Operations). Instead, staff functions were separated temporally, with a Current Operations section that focused on the 0-10 day period, a Future Operations section that focused on the 11-90 day period, and the Future Plans section which focused on the 91+ day period.

On top of this unique staff, which was unlike any other American staff I had served on, uniformed military members from over 50 Allied and partner nations comprised the staff. To make matters even more interesting, these nations also contributed other units within the Afghanistan area of operations, and each nation had a set of “national caveats” which determined how they could be used for military operations within the country.

Some nations, like the United States, Great Britain, and Australia, had almost no caveats and could be used for any kind of offensive, defensive, or peacekeeping operation with Afghanistan. Other nations, usually smaller in size and contribution to the overall effort, had heavy political caveats placed on their units, which left them being used in very niche roles, and it was almost impossible to use them for any activity not defined within those caveats.

At the time, I was a Major, which while normally being a somewhat high rank, placed me close to the bottom of the pecking order within the IJC headquarters. The legion of Majors on the staff were action officers, with specific responsibilities and expertise, and we did the bulk of the day-to-day work in the Future Plans Directorate. Our small section of planners focused on the future development of forces within a specific Regional Command, which were six administrative and operational areas of operations within Afghanistan.

I was the planner for RC-East, which bordered Pakistan on the eastern side of Afghanistan. RC-East was extremely large and geographically diverse, with 20,000-foot mountain ranges intersected by numerous river valleys stretching north to south parallel with the Pakistani border before it started to flatten out toward the Pakistani province of Baluchistan. Calling it an international border was an exaggeration, as the Pashtun tribes which populated most of RC-East crossed the border at will, except at the handful of established border crossing points that coincided with major roads crossing the border.

Organizational Planning Under Pressure

At the School of Advanced Military Studies, we had been privy to visits from the senior-most General Officers in the military. Many of the famous and well-known four-star Generals spoke to us about a series of different topics during our time as students there. One General Officer, who will remain nameless, told us a story about when he was a planner after graduating from SAMS, and although it seemed to be apocryphal, events in my near future showed that I was to suffer through the same fate as he did many moons before me.

He said that he was the lead planner for a large American military operation, and because of security concerns, had received no higher level or strategic guidance from his Commanders. In fact, he was told to watch the President’s latest press conference concerning this specific operation, which was to take place in a few days. So, like the good planner and officer he was, he listened to the press conference a few days later. Sure enough, the President had laid out the conditions for strategic and operational success, termination criteria (those are needed to terminate a war), and other interesting and vital portions of information needed to initiate a plan. As he told us this story, I said, “This is the American military, which prides itself on discipline, precision, and accuracy. There’s no way this story can be true. There’s no way that a solitary Major would be given no strategic guidance from his or her leadership, it’s just not possible!”

Fast forward to June 2011, and sure enough, I had been designated as the lead planner for IJC and had to create and build the first drawdown plan for US forces from Afghanistan. I had been working closely with my higher headquarters, the ISAF HQ, a few blocks away in Kabul, commanded by General Petraeus. Although I had asked my counterparts there (and their leadership) for any small portion of information about setting conditions for the plan, I was always told the same thing: “We don’t know anything either, and we keep asking Central Command (CENTCOM) HQ back in Tampa, and either they don’t know anything, or they aren’t sharing.”

In a state of some befuddlement, I resigned myself to my fate. So, a few days later I woke up at 3 a.m. and watch President Obama’s address to the nation from the United States Military Academy at West Point and took notes. I scribbled notes furiously as the President spoke: “We will withdraw 10,000 military personnel by the end of December 2011; with another 23,000 to be withdrawn no later than the first of July, 2012.” I thought back to my time at SAMS, and laughed out loud thinking about the anonymous general talking about his time as a lead planner.

Around 5 a.m., my boss, an American one-star General, came into the office and asked me for a brief on what the President had said during his address. I briefed him for about half an hour, and then the IJC Commander, an American three-star General, showed up. He told me to come into his office and brief him directly on the parameters of the drawdown. After I briefed him, I finally received my first set of guidance: build out at least two courses of action and come back and brief him at 7 p.m. that evening.

Lessons Learned

I retell this story because I think there is a lot to be learned from my experience during that deployment to Afghanistan, especially when it comes to the concept of strategic ambiguity.

It doesn’t matter if you are a military, government, or corporate leader – at some point, you will have to lead your organization through an ambiguous situation.

The strategic environment in the corporate and government sectors are similar in many ways. Chaos and complexity rule the roost, with financial, political, organizational, personnel, and supply factors all shifting and morphing over time. The Army uses an acronym to describe the strategic environment – VUCA – which stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. No one person can identify nor understand every piece of information out there, nor do they have the time to analyze that information. As such, senior leadership should develop processes and teams to identify and understand their organization’s place within the strategic environment. In addition, senior executives are regularly forced to react to events that have not been forecasted or expected to occur. Based on my time at IJC, here are a few pointers to navigating ambiguous situations.

- Expect the Unexpected. Even the best-laid plans go awry. Natural disasters, unforeseen economic issues, and global pandemics are just a few of the triggers leading to strategic ambiguity. It may sound blasé or cliché, but proactively accepting ambiguity is inevitable, and preparing for it with the information you have is the best way to increase your likelihood of success. Time is a critical factor here as well, and one that should be at the forefront of every senior leader’s thought process. That brings me to my next point…

- Create a Team of Strategists Focusing on the Strategic Environment. Many successful organizations have a team of strategists or futurists whose mission is to scout the strategic environment, identify emerging trends, and look at medium and long-term alternative futures in order to better understand what may lie ahead for their company or unit. Even if you don’t have those resources, spending the time yourself to study the environment your organization is operating in is invaluable when planning. And when looking into that crystal ball, don’t forget to…

- Seek Alternative Sources of Information. As I found out, you may not always get the information you need from your organization or superiors. So, when you are conducting strategic reconnaissance, consider other ways to secure the information you need to plan your way through ambiguity. For me, it was listening to the President’s address; and as I learned, the most valuable source of information may not be the most obvious.

If you find yourself working through strategic ambiguity, want to bounce an idea off someone, or need help taking stock of your operational environment, I’d love to chat. I can be reached at andrew.dziengeleski@theclearing.com

I look forward to hearing from you.

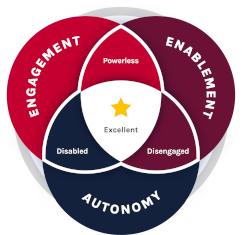

The Clearing’s Employee Experience

Improvement model, adapted from Itam

& Ghosh, 2020, focuses on three objectives:

The Clearing’s Employee Experience

Improvement model, adapted from Itam

& Ghosh, 2020, focuses on three objectives: